This article appears in our Q3 2019 Quarterly Report.1

It is a truism of course to say that it is impossible to predict the future. And typically, the further into the future you go, the harder it is to predict what is going to happen. But in some cases, forecasting what is likely to happen in the long term can be done with reasonable confidence.

At WHEB’s annual conference in July we heard from Professor Sarah Harper, Oxford University’s Professor of Gerontology. Professor Harper’s predictions are based on long-term demographic trends which play out over decades and do not change quickly. India’s labour pool is, for example, due to overtake China’s in 2029 due to deep structural changes in Chinese and Indian societies. We can be confident that this is going to happen although it may turn out to be 2028 or 2030.

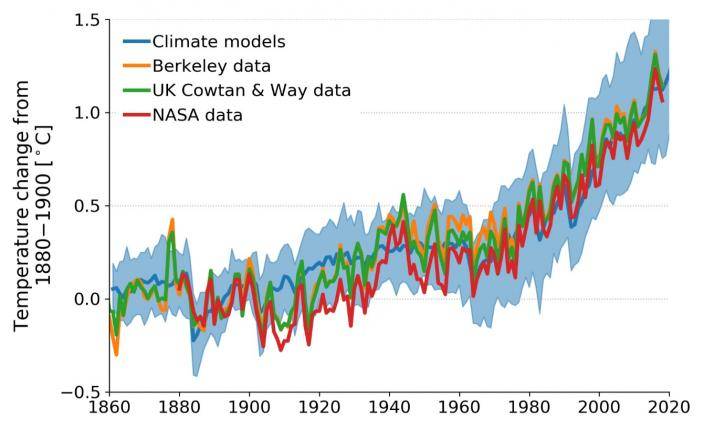

Other long-term structural trends like climate change are no different. The science of climate change is now well-understood and modelling climatic change has proven remarkably accurate. The original models that were built in the 1970s and 80s tended to under or over predict rates of warming by between 20-30%. More recent models have reduced this to high single figures and typically have tended to predict slower rates of warming than have subsequently been experienced.2 Given the continuing increases in atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases (GHG), we can anticipate with a high degree of confidence that climate change will continue along the lines that the models predict.

Even at the lower levels of warming that the models predict, there will be significant impacts. At 2 °C of warming above preindustrial levels, impacts are expected to include, among others, that:

- 37% of the earth’s population is expected to experience extreme heatwaves at least once every five years;

- 411 million people living in megacities will be exposed to severe droughts;

- 18% of insects and 16% of plants will lose more than half of their range,

- coral reefs will mostly disappear; and,

- between 32-80 million people worldwide will be exposed to flooding from sea level rise.4

The inevitable policy response

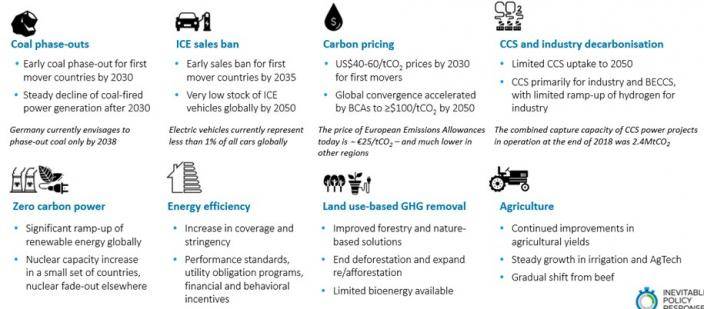

While the precise details of some of these effects are of course very difficult to predict, in aggregate it is clear that these impacts will become intolerable. For this reason, many commentators have concluded that, at some point, there will have to be an ‘inevitable policy response’ aimed at limiting and then eventually reversing climate change. The ‘Inevitable policy response’ (IPR) is the name of a UN PRI initiative that is aimed at helping investors prepare for the response from regulators as these impacts become clear. The IPR’s analysis suggests that policy commitments can be expected to accelerate in the period between 2023-2025 and that key policies will drive rapid changes in energy mix, transport technology, energy efficiency standards and agriculture (see image below).

As I write this, Extinction Rebellion have launched a new campaign of occupation in central London and, if anything, 2023 sounds like a relatively conservative date at which the policy response will begin to accelerate. As of October 2019, 1,110 jurisdictions in 20 countries covering nearly 300 million people have already declared ‘climate emergencies’ and 16 countries from the UK to Uruguay have set target dates to be net zero carbon.

Implications for the FP WHEB Sustainability Fund

Strategy alignment

Clearly accelerating action to tackle climate change is good news generally, but it is also particularly relevant for many of the sectors and technologies that the WHEB investment strategy is exposed to. This is especially true where the technologies have matured and are at or close to cost competitiveness with legacy approaches. We are particularly optimistic that strengthened performance standards around, for example, building efficiency, vehicle emissions, product energy efficiency and power generation will prove popular policy tools and will directly benefit many companies in the WHEB portfolio. Other areas highlighted by the IPR will, we believe, prove harder to address including incentivising carbon capture and storage, agriculture and land-based GHG removal and the use of hydrogen in heavy industry. In these cases, many of the technologies are still relatively small-scale and untested and policy support is likely to involve more direct fiscal support which introduces significant policy risk.

Portfolio risks

However, while clearly a strong positive for the strategy, there are two areas where more aggressive action on climate change will also create risks in the portfolio. In particular:

- Businesses delivering incrementally positive impact may find that the market begins to move away from them. For example, companies that sell technologies to improve the efficiency of internal combustion engines in vehicles may find – and indeed have already found – that the market has moved aggressively towards even better environmental impact technologies including, for example, electric vehicles. We believe that we have already positioned the fund ahead of many of these shifts but need to remain attentive to this issue.

- Certain areas that we invest in, including for example paper and cardboard recycling and water treatment, are large users of energy. As regulatory frameworks tighten on carbon emissions, these businesses are vulnerable to escalating cost and business risk. Overall the WHEB strategy is significantly lower carbon than the wider market. In 2018, Scope 1 and 2 emissions from the strategy were 65 tCO2e compared with 103 tCO2e for the wider market[4]. Furthermore, where there are high energy users in the fund, such as in those sectors identified above, the fund is invested in relatively efficient users of energy. Any increase in energy costs (for example associated with a carbon price) would therefore competitively advantage businesses we are invested in compared to their peers. Nonetheless, these companies are priorities for engagement, and we continue to work hard with them, and with other investors, to encourage more action to further reduce emissions.

2 Carbon Brief – https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-how-well-have-climate-models-projected-global-warming

3 Climate Feedback – https://climatefeedback.org/evaluation/washington-examiner-op-ed-cherry-picks-data-to-mislead-readers-about-climate-models-patrick-michaels-caleb-stewart-rossiter/

4 https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/spm/

5 https://wheb.clientprojects.co.uk/media/2019/06/WHEB-Impact-Report-2018.pdf